I spent a little time putting together this special photo album for my WWII Japanese aviation collection. I consulted two different websites and quoted their texts verbatim. One source was Wikipedia which isn’t as bad as some folks would think! As a former educator, we always held the belief that Wikipedia was not an “authoritative source” for information but that isn’t so! The other website quoted from noted historians and Japanese aviation experts. This album focuses on the “Pappy Boyington” of Japan – Sadaaki Akamatsu. He was a colorful character to say the least! He is well- regarded as the “undisputed master of the Raiden or Jack” interceptor. It is not “light reading” but it is well worth your time to read through it, especially if you have any interest in these “obscure” Japanese aviators! If not, you may still enjoy the photos…

Originally shared by Pete Panozzo

SADAAKI AKAMATSU

Sadaaki Akamatsu (赤松 貞明 Akamatsu Sadaaki, 30 July 1910 – 22 February 1980) was an officer and ace fighter pilot in the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific theater of World War II. In aerial combat over China and the Pacific, he was officially credited with destroying 27 enemy aircraft.

Akamatsu was known as a troublemaker and trickster. Many of his air victories were obtained while drunk. Despite this, his supervisors stood behind him, as did his fellow pilots who frequently defended and covered for him. Henry Sakaida confirmed that Akamatsu flew for more than 8,000 flight hours. At the end of the war, Akamatsu flew the Mitsubishi J2M Raiden fighter.[2]

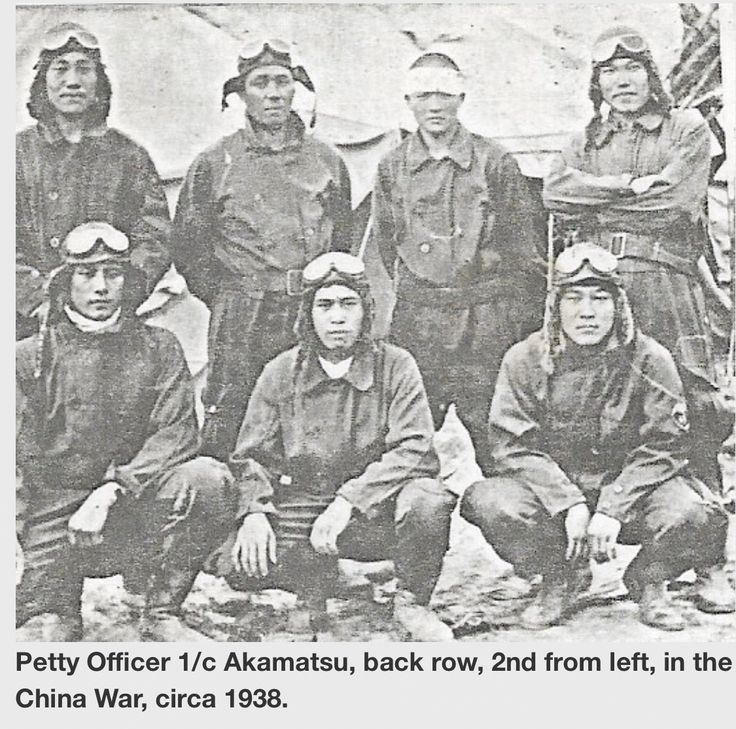

Akamatsu was credited with shooting down 11 enemy aircraft over China in the Second Sino-Japanese War, including four in a single engagement near Nanchang on 25 February 1938. In the opening months of the Pacific War, he served in the Philippines and Dutch East Indies campaigns. From January 1944 until the end of the war, Akamatsu flew out of Atsugi Air Base, defending Tokyo from Allied air attacks.

After the war, Akamatsu worked as a fish search pilot for the Kōchi Fishery Association and later ran a small cafe in Kōchi. After struggling for years with alcoholism, Akamatsu died of pneumonia on 22 February 1980.[2]

The above text from Wikipedia: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sadaaki_Akamatsu

Sadaaki Akamatsu, Japan’s “Pappy Boyington”

by Henry Sakaida

“Akamatsu stunned his superior officers by his conduct. Instead of attending pilot briefings and waiting on the flight line like the other men, he had his own warning system hooked up in a brothel! He often came racing to the air base in an old car, driving like a demon with one hand, drinking from a bottle held in the other. The sirens were screaming a warning as he bolted from the car to his fighter plane, already warmed up by the mechanics…” (Samurai! by Saburo Sakai with Martin Caidin and Fred Saito).

This reads like Hollywood fiction, and it is. Almost everything you have read about this legendary fighter ace is either false or exaggerated. And you can pin the blame on writer Martin Caidin who took enormous liberties with the truth. Sakai, who couldn’t read English, did not know this until long after the book was published in the US in 1957. Subsequent writers simply took Caidin’s “Akamatsu” and added more of their own embellishments.

To say that Akamatsu was a character is an understatement! Every Japanese Navy pilot knew of him. Whenever I mentioned his name to the surviving veteran pilots, they would chuckle and exclaim, “Oh yes, that Akamatsu!” He was a lot like our Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, the “bad boy” leader and ace of the Marine Corps’ “Blacksheep Squadron.” Our Medal of Honor recipient was born in December 1912. He was given the moniker “Pappy” because he was considered old to be a fighter pilot.

Akamatsu, born in July 1910, has the distinction of being the second oldest JNAF frontline ace to survive the war. He was eclipsed by Lt(jg) Mitsugu Mori (1908), another China War veteran, who survived the combats over Rabaul and Guadalcanal. Mori was retired in August 1944 despite a wealth of experience. Official Navy records credited him with 9+ victories (4 in China); he passed away in 1960 from illness.

Lt(jg) Sadaaki Akamatsu claimed over 350 aerial victories during the China and Pacific Wars. There is a big difference between a claim and a confirmed victory. More about this later.

Here is Akamatsu’s biography in his own words. It was written circa 1960 to an American researcher in response to his inquiry, and this copy was provided by Akamatsu’s wife after her husband’s death, and translated into English. Writing from memory and old newspaper articles about himself, there are a few errors in this great historical document.

“My father’s name was Akamatsu Sadami. He was the chief of Yokohama Weather Observation Post; he died in May 1945.”

“I entered Kainan Middle School in April 1924. I finished the 4th grade in March 1928; entered Sasebo Navy Station June 1928. Went to Kasumigaura Air Group in the 17th NCO Flying Cadet Class in May 1930. Graduated as aviation private 1st class, moved to Ohmura Air Group to learn the techniques of air combat in May 1931. Assigned to the carrier Akagi in 1933, then on the carrier Ryujo in 1934.”

“I was transferred to the Yokosuka Air Group in 1935, then to the 13th Air Group in 1938. Participated in the China War. The first aerial combat was over Nanking in 1939. It was a combat of 18 of us vs some 30 enemy planes. I shot down 3 enemy planes and confirmed it.”

“Till I returned to Japan in 1941, I destroyed over 200 enemy aircraft including confirmed, probable, burned on the ground, destroyed on the ground.”

“December 1937 to September 1938, in 13 major aerial combats 266 enemy planes including 52 probables during the period. Fighters of both 12th and 13th Air Groups destroyed 22 enemy planes at the most. This record is taken from the book edited by the War History Department.”

“On 8 December 1941, I fought against 4 P-40s, shot up one plane, but I couldn’t confirm the result. Later I fought against or strafed B-17s and P-40s but couldn’t confirm the result.”

“During 1942, I moved from Takao, Davao, Kendari, Makassar, Bali, and Kupang with Kamei unit (3rd Air Group). Over Surabaja, Java, I fought against 6 Neuport fighters (Curtiss) and shot 2 down, shot down a flying boat with two other pilots. Later, I attacked 3 Neuports by strafing. Over Bali, I shot down 2 P-40s confirmed. In this combat, some 16 enemy planes began takeoff when we arrived. We easily took our firing position; they disappeared before long. All 9 Zeroes safely returned.”

“During Ambon attack, 6 Zeroes strafed and burned 5 twin-engined bombers and a flying boat. Also shot down a B-17 probably. From Kupang, I participated in the Port Darwin attack and shot down a Spitfire.”

“Till I moved to Sabang, I destroyed 30 including on the ground and probable. At Sabang or at Nicobar Island, I shot down one flying boat with five others, lost one man west of Nicobar in 1943. On 31 December 1943 over Calcutta, I shot down a Spitfire and probably another.”

“I transferred to the 302 Air Group as lieutenant junior grade with the Raiden interceptor in January 1944. Till the end of the war, I shot down 9 Grummans (4 confirmed and 5 probables), one P-45, 7 B-29s (one confirmed and 6 probables) and one B-24. Our dogfighting techniques were superior than any other countries’ but the enemy’s shooting average is better than Japanese.”

“My memorable aerial combat is the one over Bali during WWII period. Over our homeland we were always inferior in number. I had no time to think till the end of the battle. During the period of the Type 96 fighter, it took many bullets to shoot down 4 enemy aircraft, but 20mm of the Zeroes and Raidens had less bullets, and they could only take care of two enemy planes. 7.7mm bullets could be used for strafing since it had as many bullets as the Type 96 fighter.”

“My previous wife’s name is Hisako with whom I married in 1931; she died of illness in October 1960. I had 5 children: Akiko, Nariaki, Reiko, Yoko, and Junko (one boy and four girls). My present wife is Tami with whom I married in December 1960.”

“After the war, I worked for Nishi Nippon Aircraft Association. My illness is liver disease, but now I am OK. My shop’s name is Maki. I enclose a photo which was taken by my friend on the side of a Raiden.”

“I can’t imagine the number of missions flown. At Atsugi, I once flew 7 times in one day. Till the transfer to Nanking, my flying time reached some 3,000 hours. I think at the end of the war, it stood just over 8,000 hours. I was never shot down, but was hit many times, no injury at all.”

“On Nishizawa, Kato, and Muto, I acknowledge them but I can’t help you.”

“On your P.S., on 17 February 1945, I saw white smoke out of my first Grumman, after that I couldn’t see the results because I fought against many Grummans.”

There is confusion about Akamatsu’s given name. Was it Sadaaki, Sadanori, or Temei? His formal given name is Sadaaki. Sadanori is a total error. Japanese kanji characters can be read in several ways. Bob is the nickname for Robert; Jim is a nickname for James; Bill is a nickname for William. And Temei is another reading of the kanji for Sadaaki; the famous pilot called himself Temei.

Esteemed Japanese aviation historian Sam Tagaya clarifies the confusion about Akamatsu’s name which I found very enlightening: “Akamatsu’s given name of Sadaaki. As you may know, there was a wide practice among IJN personnel of purposely reading the kanji of a person’s given name, not in its properly intended way, but using an alternate (but legitimate) reading, mainly as a joke and as a form of nickname. Yes, Sadaaki was his proper given name. But the same kanji can be read as ‘Teimei’. ‘Teimei’ sounds very close to ‘Temei’. ‘Temei’ is a very pejorative way of addressing someone in Japanese, somewhat like “Hey You” in English, but stronger in tone. Akamatsu was fond of saying that he was often called ‘Temei’ because of his many transgressions, and would say ‘Yessir, that’s my name, alright’; i.e. a self-deprecating play-on-word joke.

“Akamatsu had joined the Navy nearly ten years before my own enlistment, but failed to achieve the rapid promotions which his fellow pilots coveted. Indeed, he was even broken in rank on several occasions, and threatened with dishonorable discharge.” – Saburo Sakai, Samurai!

There is no evidence that Akamatsu was”broken in rank on several occasions.” Pilots were promoted according to schedule. His China War comrades who managed to survive until 1945 were officers by then. Veterans such as Saburo Sakai, Tetsuzo Iwamoto, Kaneyoshi Muto, Watari Handa, and Matsuo Hagiri, all NCOs from that period, are prime examples.

According to Wikipedia: “Sadaaki Akamatsu was well known, with a reputation as a trouble-maker and also a trickster. Many of his air-victories were obtained while drunk and his supervisors stood behind him, as did his fellow pilots who frequently defended and covered for him.” Young pilots were known for their rowdy horseplay, drinking, and getting into trouble, and Akamatsu wasn’t unique. He NEVER flew while intoxicated, ever! No one defended and covered for him. He was a great instructor and in combat, he was invincible.

There are some silly stories about Akamatsu which ARE true! Again, aviation historian Sam Tagaya was kind enough to contribute the following:

“There was clearly a basis for Akamatsu gaining the colorful reputation he had, all basically from his younger days. These stories come not from latter day enthusiasts, or IJN pilots who heard these stories via hearsay. They come from IJN pilots who were direct witnesses to his antics in his younger days.”

“Here are two such eyewitness stories. At one point c. 1939, Akamatsu was posted to Suzuka Kokutai and was getting thoroughly bored. He rounded up a number of other pilots and the next time they got permission to go off base they all went to stay overnight at a ‘house of ill-repute’ in the nearby town. Not wanting to put their real names on the register, at Akamatsu’s urging, they instead wrote down the names of the Suzuka Kokutai CO and other senior officers of the base. The next time the Kempeitai (military police) came around on a routine inspection of ‘off-limits’ premises, they saw these names in the register. Realizing that there was no way such senior officers would frequent a sleazy joint like this, they duly reported it to the air base. When the CO heard about this, he was livid and knew instinctively who was responsible. Akamatsu promptly got hauled on the carpet in front of the base commander and received a real grilling.”

“Another story involves a wedding ceremony for a fellow pilot. Traditional Japanese weddings are not raucous parties like in the West, but rather solemn occasions in which the bride and groom exchange ritual cups of sake and a Shinto priest presides over the ceremonies. Into this silent, sedate crowd, Akamatsu arrived late, stomping into the hall stark naked and ‘four sheets to the wind’. He had fashioned a ‘grass’ skirt out of torn strips of newspaper which he had tucked into the waist string of his fundoshi (underwear), and he proceeded to stumble through his version of a hula dance, then promptly keeled over in a corner and started snoring in a deep sleep. The family and relatives of the bride were speechless with shock. As for the invited group of IJN pilots, all buddies of the groom, and all quite familiar with Akamatsu’s occasional outbursts of outrageous behavior, it was all they could do to keep a straight face and stop from bursting out in uncontrollable laughter.”

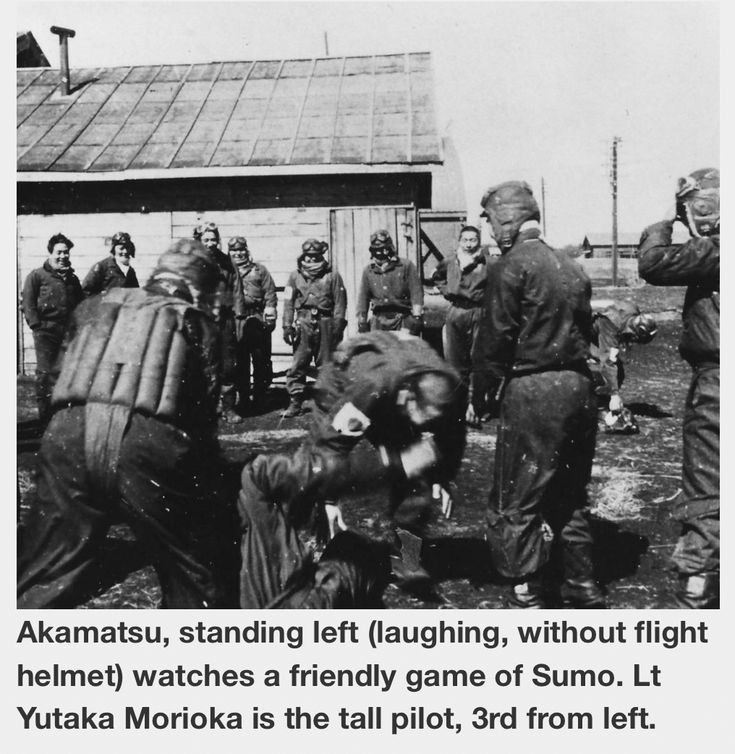

Former Lt. Yukata Morioka, the commander of a Zero squadron at Atsugi, said to me, “He was pretty wild in his China War days, but after he became an officer, he behaved himself. He obeyed orders like everyone else.”

Lt Morioka credited Akamatsu with helping him survive. He trained as a Val dive-bomber pilot, but late in the war, converted to the Zero fighter at Atsugi. In a mock dogfight with Akamatsu, the young lieutenant found his instructor on his tail even before he could take evasive action. “Hey, I’ve shot you down three times already!” laughed Akamatsu into the R/T. Before the end of the war, Morioka claimed 5 kills including a Mustang and a Hellcat (both documented from American records).

Akamatsu’s superb dogfighting skills, his victory claims, and his ability to survive when outnumbered, made him famous. “I had confidence that I would never get shot down!” he wrote in his memoirs. “This confidence helped me survive. I engaged in severe training for over 10 years. I trained physically and spiritually as a pilot every day. Through my experience, I could freely manipulate my fighter plane just like my hands and feet. This requires a training of ten years.”

Akamatsu was tough not only in the air, but also on the ground as well. Off duty pilots congregated in a small area on the airfield where they held sumo (wrestling) matches. Akamatsu was one tough hombre who seldom lost. In Judo, he was a 4th degree Blackbelt. Pappy Boyington was a champion wrestler also. Like Akamatsu, “Blacksheep One” first saw combat in China. Had they met postwar, they would have had a lot to talk about.

Sakai was incredulous when Akamatsu told him that the Raiden was the best interceptor! “It wasn’t very maneuverable, but he had no trouble in shooting down Grummans and Mustangs!” The Raiden was designed to fight B-29s and was armed with 4 x 20mm cannons. The aircraft was fast, heavy, powerful, and very demanding, but couldn’t turn on a dime like the faithful Zero. The young pilots complained about its high landing speeds and poor rear visibility. This didn’t bother Akamatsu; he loved its power, speed, and ruggedness.

In many newspaper interviews, Akamatsu boasted of shooting down over a hundred enemy planes; sometimes, it was 260 and 350. It all depended on his mood and sobriety. None of his surviving veteran comrades took his claims seriously.

In his memoir published in the early 1960s, Akamatsu wrote: “During the China Incident, there were two pilots who shot down more than my record. It is no longer possible to break my record. I am frequently asked how many enemy planes I shot down. I don’t remember exactly, but about 350. Among them, 242 or 243 were scored during the China Incident. During the Pacific War, I didn’t score as before — about a hundred something. The reason for this was because as the Pacific War progressed, the enemy fighter planes improved significantly, At the start of the war, there weren’t enough enemy planes for us to shoot down. In the later part of the war, we were outnumbered. We were so few in number that we didn’t have a chance to score.”

The claims Akamatsu made in the homeland defense seem entirely reasonable. The 302 Air Group records note that he downed 4 Hellcats on 17 February 1945 during the US carrier raids against Tokyo area targets. This was his first combat against US fighters over the homeland; he did it in two missions. He is also credited with a P-51 which he shared with his wingman on 23 June 1945. There are no other entries. Akamatsu’s claim for a P-45 was actually a P-51.

Aviation historian Jack W. Lambert, author of The Long Campaign: The History of the 15th Fighter Group in World War II (1982) wrote “Dogfighting Jacks, Todd Moore was distracted by the sight of a Zeke on the tail of a P-51. Lieutenant (jg) Sadanori Akamatsu, a legendary Japanese ace, was surrounded by the 45th Squadron, but was resolutely tearing holes in 2nd Lt. Rufu Moore’s Mustang…” Lambert wrote that Akamatsu had taken on some 75 Mustangs and shot down one. There is no evidence that Akamatsu was involved in this action of 29 May 1945. Had Akamatsu hit a Mustang, he would have claimed it.

It is interesting that Akamatsu made a claim for only one P-51 Mustang in his combat career. It was such a memorable encounter, he wrote about it in his memoir: “It was near the end of the war, after the great enemy air formations wrecked Tokyo, that I fought them. While they were returning home, we chased them. We spotted the enemy planes on the southern tip at the end of Tokyo Bay. Five of our Raidens raced in to fight. The enemy always kept the tail covered with the P-51. I hid behind one where he had a blind spot. After following for a while, I had the advantage of attack.”

“I fired my guns from very close range and hit its fuel tank. Then suddenly, he fell, on fire. The others saw this and spiraled down to attack me. I had expended all of my ammunition; I couldn’t run because they would chase me, so I made a head-on attack. I could see their tracers coming in. I was accustomed to enemy bullets. If you weren’t, then you would think that it might hit you; you would be frightened and get shot down. The enemy planes gave chase, but never separated me.”

“I thought the enemy couldn’t continue to fight because of their fuel situation. My fuel was also low and I managed to evade getting hit. I didn’t have enough fuel to land at Atsugi, so I landed at Yokosuka. Because it was a hard battle, I appreciated the brave pilot’s fight.” This was most likely the 23 June 1945 dogfight.

During the war, there was no system for the Japanese to verify aerial victory claims. There is no doubt that he was an “ace” by American standards and a “super ace” in the Imperial Navy. Dr. Yasuho Izawa, one of Japan’s most respected aviation historians, guesstimates that Akamatsu downed about 27 enemy aircraft in his career (11 scored in China), not an unreasonable figure in nearly 8 years of combat.

After the war, Akamatsu was presented with a small Piper plane which was bought with donations from his comrades. He worked briefly as a fish search pilot. Later, he sold the plane to keep him in sake. This outrageous behavior alienated his old comrades and they ostracized him. He was estranged from his children due to his alcoholism. He ran a small cafe until his death.

Sadaaki Akamatsu died at 1750 on 22 February 1980 at the Asakura Hospital in Kochi City, of acute pneumonia; he was only 70 years old.

http://ww2awartobewon.com/featured-article/sadaaki-akamatsu-japanese-pappy-boyington/

Photos from the above cited website

photo 1: LtJjg) Akamatsu at Atsugi Airfield, 1945. He was the undisputed master of the Raiden (Jack) fighter.

photo 2: Petty Officer 1/c Akamatsu, back row, 2nd from left, in the China War, circa 1938.

photo 3: Akamatsu, standing left (laughing, without flight helmet) watches a friendly game of Sumo. Lt Yutaka Morioka is the tall pilot, 3rd from left.

photo 4: J2M Raidens (Allied codename: Jack) of the 302 Air Group at Atsugi. The 3 aircraft lined up diagonally on the left all have victory markings on the top of their tails.

Recent Comments