A recent post that I created on the famous WWII Japanese ace Hiroyoshi Nishizawa.

Originally shared by Pete Panozzo

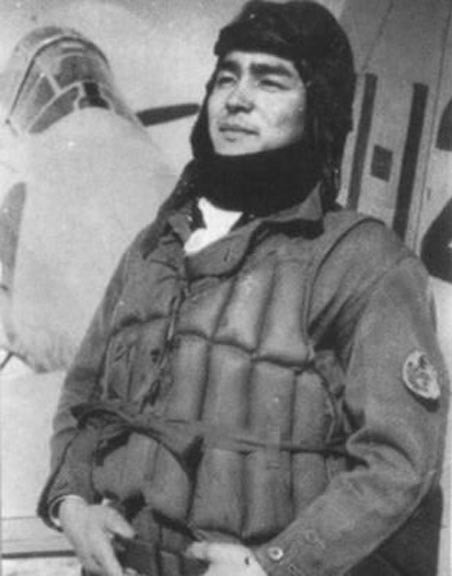

HIROYOSHI NISHIZAWA

Lieutenant Junior Grade Hiroyoshi Nishizawa (西澤 広義 Nishizawa Hiroyoshi, January 27, 1920 – October 26, 1944) was an ace of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service during World War II.

He is officially credited in Japan with the following aerial victories:[citation needed]

victories – 36

damaged – 2

shared damaged – 49

It is possible that Nishizawa was the most successful Japanese fighter ace of the war; he personally claimed to have had 102 aerial victories at the time of his death. Some uncertainty is due to the Japanese habit of recording victories for pilots’ units, rather than the individual, after 1941, as well as the often wildly exaggerated claims of aerial kills that were frequently accepted.[citation needed] Some sources credit Nishizawa with over 120 to 150 victories.[1][2]

Hiroyoshi Nishizawa was born 27 January 1920 in a mountain village in the Nagano Prefecture, the fifth son of Mikiji and Miyoshi Nishizawa. His father was the manager of a sake brewery. Hiroyoshi graduated from higher elementary school and then began to work in a textile factory.

In June 1936, a poster caught his eye, an appeal for volunteers to join the Yokaren (flight reserve enlistee training program). Nishizawa applied and qualified as a student pilot in Class Otsu No. 7 of the Japanese Navy Air Force (JNAF). He completed his flight training course in March 1939, graduating 16th out of a class of 71. Before the war, he served with the Oita, Omura and Suzuka Kōkūtai (air groups/wings). In October 1941, he was transferred to the Chitose Kōkūtai, with the rank of petty officer 1st class.

New Guinea Edit

After the outbreak of war with the Allies, Nishizawa’s squadron (chutai) from the Chitose Air Group, then flying the obsolete Mitsubishi A5M, moved to Vunakanau airfield on the newly taken island of New Britain. The squadron received its first Mitsubishi Zeros (A6M2, Model 21) the same week.

On 3 February 1942, Nishizawa, still flying an obsolete A5M, claimed his first aerial kill of the war, a PBY Catalina; historians have established, however, that the plane was only damaged and managed to return to base. On February 10, Nishizawa’s squadron was transferred to the newly formed 4th Air Group. As new Zeros became available, Nishizawa was assigned an A6M2 bearing the tail code F-108.

On 1 April 1942, Nishizawa’s squadron was transferred to Lae, New Guinea and assigned to the Tainan Air Group. There he flew with aces Saburō Sakai and Toshio Ōta in a chutai (squadron) led by Junichi Sasai. Sakai described his friend Nishizawa as about 5-foot-8, 140 lb (64 kg) in weight, pale and gaunt, suffering constantly from malaria and tropical skin diseases. Accomplished at judo, his squadron mates, who nicknamed him the “Devil,” considered him a reserved, taciturn loner. Of his performance in the air, Sakai, himself one of Japan’s leading aerial aces, wrote, “Never have I seen a man with a fighter plane do what Nishizawa would do with his Zero. His aerobatics were all at once breathtaking, brilliant, totally unpredictable, impossible, and heart-stirring to witness.”

They often clashed with United States Army Air Forces and Royal Australian Air Force fighters operating from Port Moresby. Nishizawa’s first confirmable solo kill, of a USAAF P-39 Airacobra, was on April 11. He claimed six more kills in a 72-hour period from 1–3 May, making him a confirmed fighter ace.

Nishizawa was a member of the famed “Cleanup Trio” with Saburō Sakai and Toshio Ōta.In the night of 16 May, Nishizawa, Sakai and Ōta were listening at the lounge room to a broadcast of an Australian radio program, when Nishizawa recognized the eerie Danse Macabre of the French composer, pianist and organist Camille Saint-Saëns. Nishizawa, thinking about this mysterious skeleton dance, now suddenly had a crazy idea: “you know the mission tomorrow at Port Moresby? Why don’t we perform a little show, a dance of death of our own? We do a few demonstration loops right over the enemy airfield, this should drive them crazy on the ground.”

On 17 May 1942, Lieutenant Commander Tadashi “Shosa” Nakajima led the Tainan Ku on a mission to Port Moresby, with Sakai and Nishizawa as his wingmen. As the Japanese formation re-formed for the return flight, Sakai signaled Nakajima, that he was going after an enemy aircraft and peeled off. Minutes later, Sakai was over Port Moresby again, to keep his rendezvous with Nishizawa and Ōta. The trio now performed aerobatics, three tight loops in close formation. After that, a jubilant Nishizawa indicated that he wanted to repeat the performance. Diving to 6,000 ft (1,800 m), the three Zeros did three more loops, still without any AA fire from the ground. They headed then back to Lae, arriving 20 minutes after the rest of the Kōkūtai.

At about 21:00, Lieutenant Junichi Sasai wanted them in his office, immediately. When they arrived, Sasai held up a letter. “Do you know where I got this thing?” he shouted. “No? I’ll tell you, you fools; it was dropped on this base a few minutes ago, by an enemy intruder!” The letter, written in English, said:[3]

To the Lae Commander: “We were much impressed with those three pilots who visited us today, and we all liked the loops they flew over our field. It was quite an exhibition. We would appreciate it if the same pilots returned here once again, each wearing a green muffler around his neck. We’re sorry we could not give them better attention on their last trip, but we will see to it that the next time they will receive an all-out welcome from us.”

Nishizawa, Sakai and Ōta stood at stiff attention and tried to suppress laughing out loud, while Lieutenant Sasai dressed them down over their “idiotic behavior” and prohibited them from staging any more aerobatic shows over enemy airfields. The Tainan Kōkūtai’s three leading aces secretly agreed, that the aerial choreography had been worth it.

In early August 1942, the air group moved to Rabaul, immediately operating against the US forces on Guadalcanal. In the first clash on 7 August, Nishizawa claimed six F4F Wildcats (historians have confirmed two kills)[who?].

On 8 August 1942, Saburō Sakai, Nishizawa’s closest friend, was severely wounded in combat with U.S. Navy Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bombers. Nishizawa noticed that Sakai was missing and went into a mad rage, he searched the area, both for signs of Sakai and for Americans to fight, presumably even if he had to ram them. Eventually, he cooled off and returned to Lakunai. Later, to everyone’s amazement, the seriously wounded Sakai arrived. Struck in the head by a bullet, covered with blood and blind in one eye, he returned to base in his damaged Zero after a four-hour, 47-minute flight over 560 nmi (1,040 km; 640 mi). Nishizawa, Lieutenant Sasai and Toshio Ōta transported the obstinate but unconscious Sakai to the hospital. In frustrated concern, Nishizawa physically removed the waiting driver and personally drove Sakai, as quickly but as gently as possible, to the surgeon. Sakai was evacuated to Japan on August 12.

The extended conflict over Guadalcanal was costly for Nishizawa’s air group (renamed the 251st in November) as American aircraft and tactics improved: Sasai (with 27 victories) was shot down and killed by Captain Marion E. Carl on 26 August 1942, and Ōta (34 kills) was killed on 21 October 1942.

Return to Japan

In mid-November, the 251st was recalled to Toyohashi air base in Japan to replace its losses, with the ten surviving pilots all being made instructors, including Nishizawa. Nishizawa is believed to have had around 40 full or partial aerial victories by this time (some sources claim 54).

Nishizawa, while staying in Japan, visited Saburō Sakai, who was still recuperating in the Yokosuka hospital. Nishizawa complained to Sakai of his new duty as an instructor: “Saburō, can you picture me running around in a rickety old biplane, teaching some fool youngster how to bank and turn, and how to keep his pants dry?” Nishizawa also ascribed the loss of most of their comrade pilots to the ever increasing material advantage of the Allied forces, the improved U.S. aircraft and tactics. “It’s not as you remember, Saburō,” he said. “There was nothing I could do. There were just too many enemy planes, just too many.” Even so, Nishizawa could not wait to return to combat. “I want a fighter under my hands again,” he said. “I simply have to get back into action. Staying home in Japan is killing me.”

Nishizawa publicly chafed at the months of inaction in Japan. He and the 251st returned to Rabaul in May 1943. In June 1943, Nishizawa’s achievements were honored by a gift from the commander of the 11th Air Fleet, Vice Admiral Jin’ichi Kusaka. Nishizawa received a military sword inscribed “Buko Batsugun” (“For Conspicuous Military Valor”). He was then transferred to the 253rd Air Group on New Britain in September. In November, he was promoted to warrant officer and reassigned to training duties in Japan with the Oita Air Group.

In February 1944, he joined the 203rd Air Group, operating from the Kurile Islands, away from heavy action.

In October, however, the 203rd was transferred to Luzon. Nishizawa and four others were detached to a smaller airfield on Cebu.

On 25 October 1944, Nishizawa led the fighter escort consisting of four A6M5s, flown by Nishizawa, Misao Sugawa, Shingo Honda and Ryoji Baba for the first major kamikaze attack of the war, targeting Vice Admiral Clifton Sprague’s “Taffy 3” task force, which was protecting the landings in the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

The kamikaze volunteers, led by Lieutenant Yukio Seki, piloted five bomb-armed A6M2 Model 21 Zeros, each carrying a 250 kg (550 lb) bomb. They deliberately crashed their planes into U.S. warships in the first official kamikaze attack of the Tokkōtai suicide squadron “Shikishima”. They were the first kamikazes to sink an enemy ship. The attack was very successful, as four of the five kamikazes struck their targets and inflicted heavy damage. An A6M2 likely flown by Seki[4] crashed onto the flight deck of the escort carrier USS St. Lo at 10:53. The Zero’s 250 kg (550 lb) bomb exploded on the portside hangar deck, resulting in a fire and secondary explosions which soon detonated torpedoes and the bomb magazine of St. Lo. The escort carrier sank half an hour later; 126 men were lost in action. Seki is recorded as saying before the mission: “Japan’s future is bleak if it is forced to kill one of its best pilots. I am not going on this mission for the Emperor or for the Empire… I am going because I was ordered to!” [5]

While flying fighter escort to this kamikaze mission, Nishizawa recorded at minimum, his 86th and 87th victories (both Grumman F6F Hellcats), the final aerial victories of his career.[6]

Nishizawa had a premonition during the flight; he saw in a vision his own death. Nishizawa reported the sortie’s success to Commander Nakajima after returning to base. He then volunteered to take part in the next day’s Tokkōtai kamikaze mission. His request was refused.

Instead, Nishizawa’s A6M5 Zero was armed with a 250 kg (550 lb) bomb and flown by Naval Air Pilot 1st Class Tomisaku Katsumata. A less experienced pilot, he nevertheless dove into the escort carrier USS Suwanee off Surigao. Katsumata crashed on Suwanee’s flight deck and careened into a torpedo bomber which had just been recovered. The two planes erupted upon contact as did nine other planes on her flight deck. Although the ship was not sunk, she burned for several hours, and 85 of her crewmen were killed, 58 were missing and 102 wounded.

The following day, his own Zero having been destroyed, Nishizawa and other pilots of the 201st Kōkūtai boarded a Nakajima Ki-49 Donryu (“Helen”) transport aircraft and left Mabalacat on Pampanga in the morning, to ferry replacement Zeros from Clark Field on Luzon.

Over Calapan on Mindoro Island, the Ki-49 transport was attacked by two F6F Hellcats of VF-14 squadron from the fleet carrier USS Wasp and was shot down in flames. Nishizawa died as a passenger, probably the victim of Lt. j.g. Harold P. Newell, who was credited with a “Helen” northeast of Mindoro that morning.

Upon learning of Nishizawa’s death, the commander of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, honored Nishizawa with a mention in an all-units bulletin and posthumously promoted him to the rank of lieutenant junior-grade. Nishizawa was also given the posthumous name Bukai-in Kohan Giko Kyoshi, a Zen Buddhist phrase that translates: “In the ocean of the military, reflective of all distinguished pilots, an honored Buddhist person.” Because of the confusion towards the end of the Pacific war, the bulletin’s publication was delayed and funeral services were not held until December 2, 1947.

Recent Comments